History of Yellowstone: America’s First National Park and Its Legacy

Why Yellowstone's Creation Changed Conservation Forever

History of Yellowstone: America's First National Park and Its Legacy begins on March 1, 1872, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed groundbreaking legislation that created the world's first national park. This single act transformed over 2 million acres of wilderness into a "public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

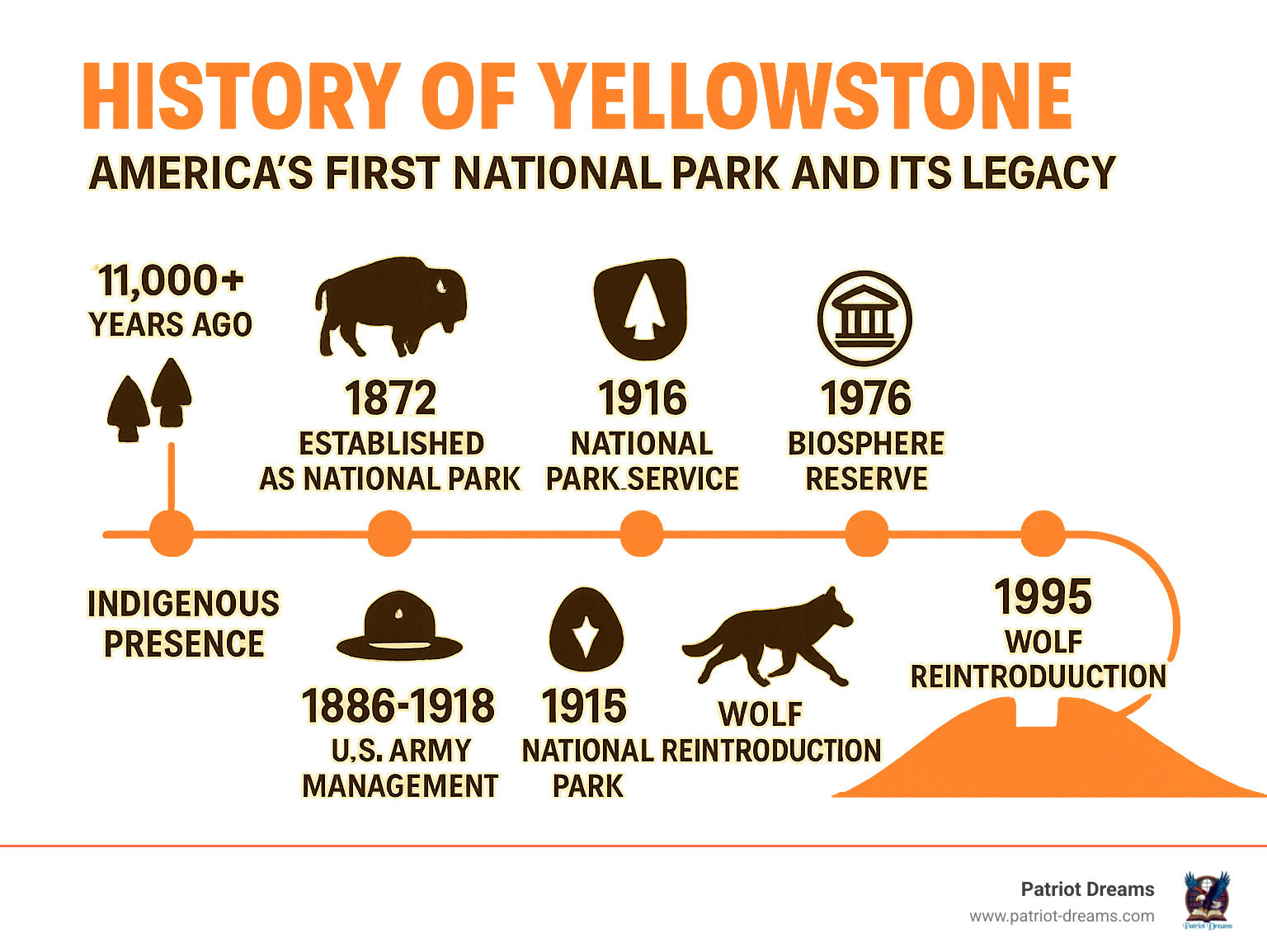

Key milestones in Yellowstone's history:

- 11,000+ years ago - Indigenous peoples establish continuous presence

- 1872 - Established as world's first national park

- 1886-1918 - U.S. Army manages and protects the park

- 1916 - National Park Service takes over management

- 1976 - Designated UNESCO Biosphere Reserve

- 1978 - Becomes World Heritage Site

- 1995 - Wolves successfully reintroduced

The park's creation wasn't just about preserving over 10,000 hydrothermal features, which was more than the rest of the world combined. It established a radical idea that natural wonders should belong to everyone, not just wealthy private owners.

Yet this legacy carries complexity. While celebrated as untouched wilderness, Yellowstone was actually the homeland of at least 27 federally-recognized Native American tribes for millennia. The park's establishment forced these communities from their ancestral lands, a painful chapter often overlooked in traditional histories.

Today, Yellowstone stands as both a conservation success story and a reminder that preserving our heritage means telling complete, honest stories about our past.

The Land Before the Park: Indigenous Homelands and Early Exploration

Long before it was a park, the History of Yellowstone began over 11,000 years ago. For millennia, this land was home to Indigenous peoples who established deep connections to its mountains, valleys, and geysers.

They were the original stewards who understood its hot springs, animal migrations, and seasonal changes. At least 27 federally-recognized Tribes have deep connections to this region, including the Tukudika (Sheepeaters), who lived intimately with the land.

The towering Obsidian Cliff was a treasure trove, providing volcanic glass for tools and trade goods. Archaeologists have found over 50 ancient obsidian quarry sites in the park, testament to generations of skilled craftspeople.

When Euro-Americans arrived, they promoted the myth of an untouched wilderness, erasing thousands of years of Indigenous history. This false narrative was later used to justify forcing Native peoples from their ancestral homeland.

The first non-Native explorers were fur trappers in the early 1800s. John Colter, who explored the region around 1807-1808, returned with tales of geysers and bubbling mud, an area skeptics dubbed "Colter's Hell."

Jim Bridger, another mountain man, spun tales of glass mountains and boiling rivers. While many dismissed these as tall tales, they were actually understated descriptions of Yellowstone's geothermal features.

The Complicated Indigenous History of Yellowstone: America's First National Park and Its Legacy

The creation of Yellowstone in 1872 was a conservation triumph, but it came at a devastating cost for the Indigenous peoples who called this land home. What followed was a campaign of forced deterrence that made Native Americans trespassers on their own ancestral territory.

Park officials actively prevented tribes from entering, relocating the Tukudika and other groups to reservations far from their resources. Traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering became illegal, severing ancient community connections.

Park administrators also perpetuated myths that Indigenous peoples feared the geothermal features. This fiction helped justify their exclusion and reinforced the false narrative of an untouched wilderness, deliberately erasing the truth of their millennia-long harmonious existence.

Today, we're working to correct this historical injustice. Twenty-seven federally-recognized Tribes maintain connections to Yellowstone: the Assiniboine and Sioux, Blackfeet, Cheyenne River Sioux, Coeur d'Alene, Comanche, Colville Reservation, Crow, Crow Creek Sioux, Eastern Shoshone, Flandreau Santee Sioux, Gros Ventre and Assiniboine, Kiowa, Little Shell Chippewa, Lower Brule Sioux, Nez Perce, Northern Arapaho, Northern Cheyenne, Salish and Kootenai, Shoshone-Bannock, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Spirit Lake Tribe, Standing Rock Sioux, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Umatilla, Wind River Shoshone, and Yakama.

Our understanding continues evolving as modern tribal engagement efforts work to restore these vital relationships. The park now collaborates with tribal nations on everything from wildlife management to cultural education, slowly healing wounds that have festered for over a century.

This complicated legacy reminds us that even our greatest conservation successes carry complex human stories – stories that deserve to be told with honesty, respect, and hope for a more inclusive future.

The Birth of an Idea: How Yellowstone Became the World's First National Park

Picture America in the 1870s: railroads stretching across the continent, cities growing rapidly, and a national mindset focused on turning wilderness into profit. The idea of Manifest Destiny drove most decisions about public land – get it into private hands as quickly as possible for development and economic gain.

In this context, the notion of preserving millions of acres just for people to visit and enjoy seemed almost absurd. Yet that's exactly what happened with Yellowstone – a concept that emerged from an era obsessed with expansion and exploitation.

The change from tall tales to national treasure began with serious scientific exploration. After decades of wild stories from mountain men, organized expeditions finally set out to document what was really there. The Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition of 1870 proved to be a turning point. Legend has it that around a campfire where the Firehole and Gibbon Rivers meet, expedition members discussed the idea of protecting this incredible place as a public park rather than letting it be carved up for private profit.

But it was the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 that truly changed everything. Ferdinand V. Hayden, who became Yellowstone's "first and most enthusiastic advocate," understood something crucial: people needed to see these wonders to believe them.

Hayden made two brilliant decisions. He brought photographer William Henry Jackson and painter Thomas Moran along on his expedition. Jackson's photographs provided undeniable proof that geysers like Old Faithful actually existed – no more dismissing these features as frontier fiction. Moran's stunning paintings, especially "The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone," captured the area's beauty in vivid colors that black-and-white photographs couldn't convey.

When these visual masterpieces were displayed in Congress, they had an immediate impact. As Captain Hiram M. Chittenden later noted, Moran's paintings and Jackson's photographs convinced lawmakers "more than reports or speeches ever could" that Yellowstone deserved protection. You can see some of Thomas Moran's influential works here.

Advocating for a National Treasure

The campaign to protect Yellowstone focused on preserving what advocates called "the curiosities" - the region's absolutely unique geological features. And unique they truly were. Yellowstone contains over 10,000 hydrothermal features, which is more than the rest of the world combined. These include world-famous geysers like Old Faithful, rainbow-colored hot springs, bubbling mudpots, and steaming fumaroles.

All this geothermal activity stems from the massive Yellowstone Caldera, a roughly oval basin measuring 30 by 45 miles. This caldera formed from cataclysmic volcanic eruptions, with the most recent major event occurring about 640,000 years ago. The underground magma that remains powers the park's incredible thermal displays.

Supporters also made practical arguments for creating the park. As historian Patricia Limerick observed, "No one could think of anything useful to do with it." The high, mountainous terrain wasn't suitable for farming or major development, making it economically "worthless" by 1870s standards.

This apparent drawback became Yellowstone's salvation. The growing railroad industry, particularly the Northern Pacific Railroad, recognized the tourism potential. A spectacular destination would attract passengers and boost profits - giving the park proposal some powerful corporate backing.

The lobbying effort intensified through 1871 and early 1872. Hayden's compelling evidence, combined with Moran's artistic documentation and Jackson's photographic proof, built momentum in Congress. The idea of preventing private exploitation of these natural wonders while making them accessible to all Americans began to resonate.

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act into law. This groundbreaking legislation set aside over 2 million acres "as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

This was truly unprecedented – a complete departure from America's prevailing land policies. While Mongolia had protected Bogd Khan Uul in 1783, Yellowstone established the modern national park concept that would spread worldwide. The act created a new global model for conservation, providing a blueprint that countries around the world would eventually follow.

For more details about Yellowstone's global significance, you can explore the UNESCO World Heritage Centre's page on Yellowstone and this National Geographic article on the world's first national parks.

For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People: Early Challenges and Management

Creating Yellowstone was one thing – actually managing it was entirely another challenge. Yellowstone National Park nearly ended before it truly began, thanks to a perfect storm of problems that threatened to destroy the world's first national park.

Nathaniel Langford, appointed as Yellowstone's first superintendent, faced an impossible task. He received no salary, no staff, and virtually no budget to protect over 2 million acres of wilderness. Imagine trying to guard an area larger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined with nothing but good intentions!

The results were predictably disastrous. Poachers slaughtered bison by the hundreds, selling their valuable hides while leaving carcasses to rot. Vandals chipped away at delicate geological formations, taking pieces of geysers and hot springs home as souvenirs. Entrepreneurs set up unauthorized businesses, and some visitors even tried to stuff soap into geysers to force eruptions for their entertainment.

Without proper funding or legal authority to enforce regulations, the park was essentially defenseless. Resource exploitation ran rampant as people treated Yellowstone like their personal playground rather than a protected treasure. The situation grew so dire that Congress, frustrated with the ineffective administration, completely refused to provide funding by 1886.

From Army Stewards to the National Park Service

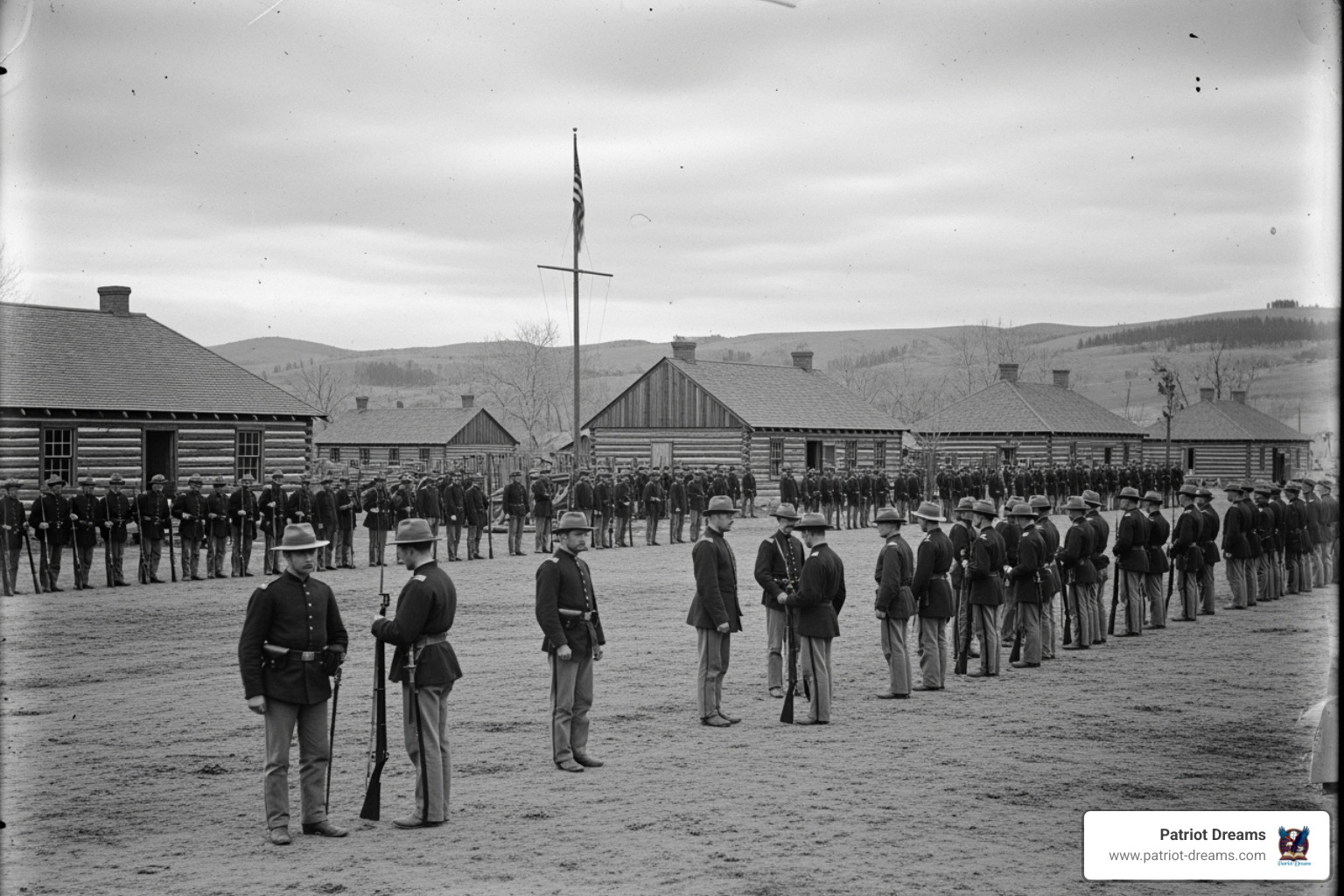

Desperate times called for desperate measures. The Secretary of the Interior made an unusual request to the Secretary of War: could the military take over? On August 20, 1886, the U.S. Army officially assumed control of Yellowstone, beginning what would become a 32-year period of military management.

The Army's approach was refreshingly direct. They established Fort Yellowstone at Mammoth Hot Springs and immediately began bringing order to chaos. Soldiers patrolled the wilderness on horseback, guarded popular attractions, and weren't shy about evicting troublemakers. Finally, Yellowstone had protectors with both the authority and backbone to enforce the rules.

One incident perfectly illustrates how the Army's presence changed everything. In 1894, a notorious poacher named Ed Howell was caught red-handed slaughtering bison in the park's remote Pelican Valley. His arrest created a media sensation when journalist Emerson Hough reported the story in Forest & Stream magazine. The public outrage that followed directly led to the Park Protection Act (also known as the Lacey Act) later that year, giving park managers the legal tools they desperately needed to prosecute criminals.

The Army didn't just stop the bleeding – they established many fundamental management practices still used today. They built essential infrastructure, created visitor services, and oversaw important boundary adjustments in 1929 and 1932 that better protected crucial wildlife habitats and winter ranges for elk and other animals.

By the early 1900s, it became clear that America's growing collection of national parks needed something more than military oversight. Park visitation was exploding, reaching one million visitors annually by 1948. The parks required dedicated civilian management that understood both conservation and hospitality.

The solution came on August 25, 1916, when President Woodrow Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act, creating the National Park Service. This new agency faced a delicate balancing act: making parks accessible and enjoyable for everyone while preserving them for future generations.

The transition from Army to National Park Service management happened gradually between 1916 and 1918. Early leaders like Horace Albright worked tirelessly to professionalize park rangers and develop consistent policies across all parks. They focused on building roads and visitor facilities while maintaining the natural integrity that made places like Yellowstone so special.

The Army's 32-year stewardship had truly saved Yellowstone from destruction, establishing order and creating the foundation for modern park management. Their legacy lives on in every visitor who can still witness Old Faithful's eruptions and hear wolves howl in the wilderness – experiences that might have been lost forever without their intervention.

The Evolving Park: Milestones, Science, and Modern Management

The History of Yellowstone: America's First National Park and Its Legacy evolved through the 20th century, shaped by world events, science, and nature itself.

During World War II, Yellowstone saw staff leave for service, a drop in visitors, and reduced funding. Proposals to use park resources for the war effort were rejected, keeping its treasures protected.

After the war, Americans flocked to national parks. This new popularity, however, overwhelmed park infrastructure. The solution was "Mission 66," a 10-year program launched in 1955 to modernize facilities. Yellowstone received new visitor centers and improved roads to welcome more guests while protecting the park.

The powerful 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake was a stark reminder of the park's dynamic geology. The 7.2 magnitude tremor triggered landslides, created Earthquake Lake, and altered Old Faithful's eruption patterns.

Perhaps no recent event shaped the park more than the 1988 Yellowstone fires, which burned approximately 793,880 acres. Many feared the park was destroyed.

The fires, however, taught a profound lesson. Scientists realized fire is essential to Yellowstone's ecosystem for renewal, clearing old growth and enriching soil. Today, managers allow natural fires to burn under specific conditions, trusting nature's process.

The wolf reintroduction in 1995 was another turning point. After being eliminated by 1926, bringing wolves back helped heal the entire ecosystem. Their return led to a "trophic cascade," as their predation on elk allowed plants like aspen and willow to recover, which in turn benefited other species like beavers. You can read more about this success story in this NPS page about Yellowstone wolves.

Recognizing its global importance, Yellowstone was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1976 and a World Heritage Site in 1978.

The Scientific and Research History of Yellowstone: America's First National Park and Its Legacy

Yellowstone is also one of the world's most important natural laboratories, where scientists uncover secrets that benefit everyone.

The park's bison herd is the oldest and largest public herd in the U.S. Management is complex, balancing conservation with challenges like brucellosis, a disease that could affect nearby cattle.

Grizzly bear recovery is a major success. Once endangered in the ecosystem, careful management has helped their population rebound, with scientists monitoring them to ensure their future.

Conservation efforts also focus on the native Yellowstone cutthroat trout, threatened by invasive species and disease. Researchers work to restore their populations, vital for the park's aquatic ecosystems.

Findings from Yellowstone's hot springs have had global impact. Scientists found thermophiles (heat-loving microbes), including Thermus aquaticus. An enzyme from this microbe, Taq polymerase, was essential for PCR, revolutionizing DNA research.

More recently, "Hadesarchaea" microbes found living on toxic gases deep beneath hot springs expand our understanding of life's possibilities, even on other planets.

Geological monitoring is constant, as the park sits on a supervolcano. The Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO) watches for seismic activity and other changes, reminding us of the powerful forces below.

Climate change presents new challenges. In June 2022, for example, record flooding damaged infrastructure and forced closures. Such events test the park's resilience and provide valuable data on ecosystem adaptation.

All this research helps managers make informed decisions, demonstrating how science and conservation work together to preserve our natural heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions about the History of Yellowstone

Why is Yellowstone the first national park?

When President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act on March 1, 1872, he created something the world had never seen before. Yellowstone became the first area anywhere to be officially designated as a national park by a federal government.

What made this so groundbreaking? At a time when America was focused on westward expansion and turning public lands into private profit, the idea of preserving over 2 million acres for everyone seemed almost crazy. The History of Yellowstone: America's First National Park and Its Legacy began with a radical concept: some places are too special to be owned by just one person.

The law specifically set aside this land "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" – not for mining, logging, or private development. This was radical thinking that established the blueprint for the entire global national park movement. Countries around the world would later follow America's lead, creating their own national parks based on the Yellowstone model.

What was Yellowstone before it was a park?

Here's where the story gets more complex. The idea that Yellowstone was an empty wilderness waiting to be "found" is simply not true. For more than 11,000 years, the Yellowstone region was home to Indigenous peoples who knew every trail, every hot spring, and every seasonal migration route.

At least 27 federally-recognized tribes have ancestral connections to this land. They didn't just pass through – they lived here. They hunted bison and elk, fished the rivers, gathered plants for food and medicine, and quarried obsidian from places like Obsidian Cliff to make tools and weapons. The Tukudika people, also known as the Sheepeaters, were especially connected to the high country.

These communities held spiritual ceremonies at the geothermal features and developed sophisticated knowledge about the landscape's rhythms and resources. They actively shaped the environment through controlled burns and wildlife management. When Euro-American explorers like John Colter and Jim Bridger arrived in the early 1800s, they were entering a landscape that had been carefully tended by Indigenous stewards for millennia.

The myth of "untouched wilderness" unfortunately helped justify forcing these original inhabitants from their ancestral lands when the park was established.

How did the U.S. Army save Yellowstone?

By the 1880s, Yellowstone was in serious trouble. The park's first superintendent, Nathaniel Langford, had no salary, no staff, and virtually no authority to stop the chaos unfolding across the landscape. Poachers were slaughtering bison by the hundreds, visitors were chipping off pieces of geysers as souvenirs, and vandals were carving their names into natural formations.

Congress got so frustrated with the mess that in 1886, they basically threw up their hands and called in the cavalry – literally. The U.S. Army took over management and immediately brought military discipline to the situation.

From Fort Yellowstone at Mammoth Hot Springs, soldiers patrolled the backcountry on horseback, arrested poachers, and established the first real visitor services. When they caught notorious poacher Ed Howell killing bison in 1894, the public outcry helped pass the Lacey Act, which finally gave park managers the legal tools they needed to prosecute criminals.

For 32 years (1886-1918), these Army rangers protected Yellowstone's wildlife and natural features. They built the foundation for modern park management and proved that with proper resources and authority, America's natural treasures could be preserved for future generations. When the National Park Service was created in 1916, they inherited a park that was finally safe and well-organized.

Conclusion

The History of Yellowstone: America's First National Park and Its Legacy tells a story that's far more complex and fascinating than most people realize. What started as a radical idea in 1872 has become the blueprint for conservation efforts worldwide, inspiring the creation of national parks on every continent.

Yellowstone's influence extends far beyond its borders. The concept of setting aside spectacular landscapes "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people" sparked a global movement. From Canada's Banff National Park to Australia's Royal National Park, countries around the world followed America's lead in protecting their natural treasures.

But perhaps the most important part of Yellowstone's legacy is how our understanding continues to evolve. We've moved from viewing it as an "untouched wilderness" to recognizing the 11,000-year history of Indigenous stewardship. We've learned that fire isn't always an enemy – sometimes it's exactly what the forest needs. The return of wolves showed us how one species can transform an entire ecosystem.

Today, Yellowstone serves as a living laboratory where scientists study everything from tiny heat-loving microbes to massive geological forces. Climate change brings new challenges, from record flooding to shifting wildlife patterns. Yet the park continues to adapt and teach us about resilience.

The ongoing challenges are real. Balancing millions of visitors with wildlife protection isn't easy. Managing bison herds while addressing disease concerns requires constant attention. Monitoring the supervolcano beneath our feet reminds us that nature operates on its own timeline.

At Patriot Dreams, we're passionate about sharing these complete, honest stories that shaped our nation. Yellowstone's history isn't just about pretty landscapes – it's about vision, mistakes, learning, and growth. It's about recognizing that preservation and progress can work together when we're willing to listen and adapt.

The park's story continues to unfold every day, reminding us that our natural heritage belongs to all of us. From the Indigenous peoples who first called it home to the millions of visitors who find wonder in its geysers and wildlife, Yellowstone connects us all to something larger than ourselves.

Listen to stories of Yellowstone and other national parks at Patriot Dreams

Join the Patriot Dreams Community

Download the app today and start your journey through American history and personal legacy.

Explore Our Latest Insights

Dive into stories that shape our American legacy.