An Essential Guide to Abigail Adams' Life

The Remarkable Spirit of a Founding Mother

Abigail Adams was the wife of America's second president, John Adams, and the mother of its sixth president, John Quincy Adams. But she was so much more than these titles suggest. She was a brilliant thinker, a passionate advocate for women's rights and education, and one of the most prolific letter writers in American history.

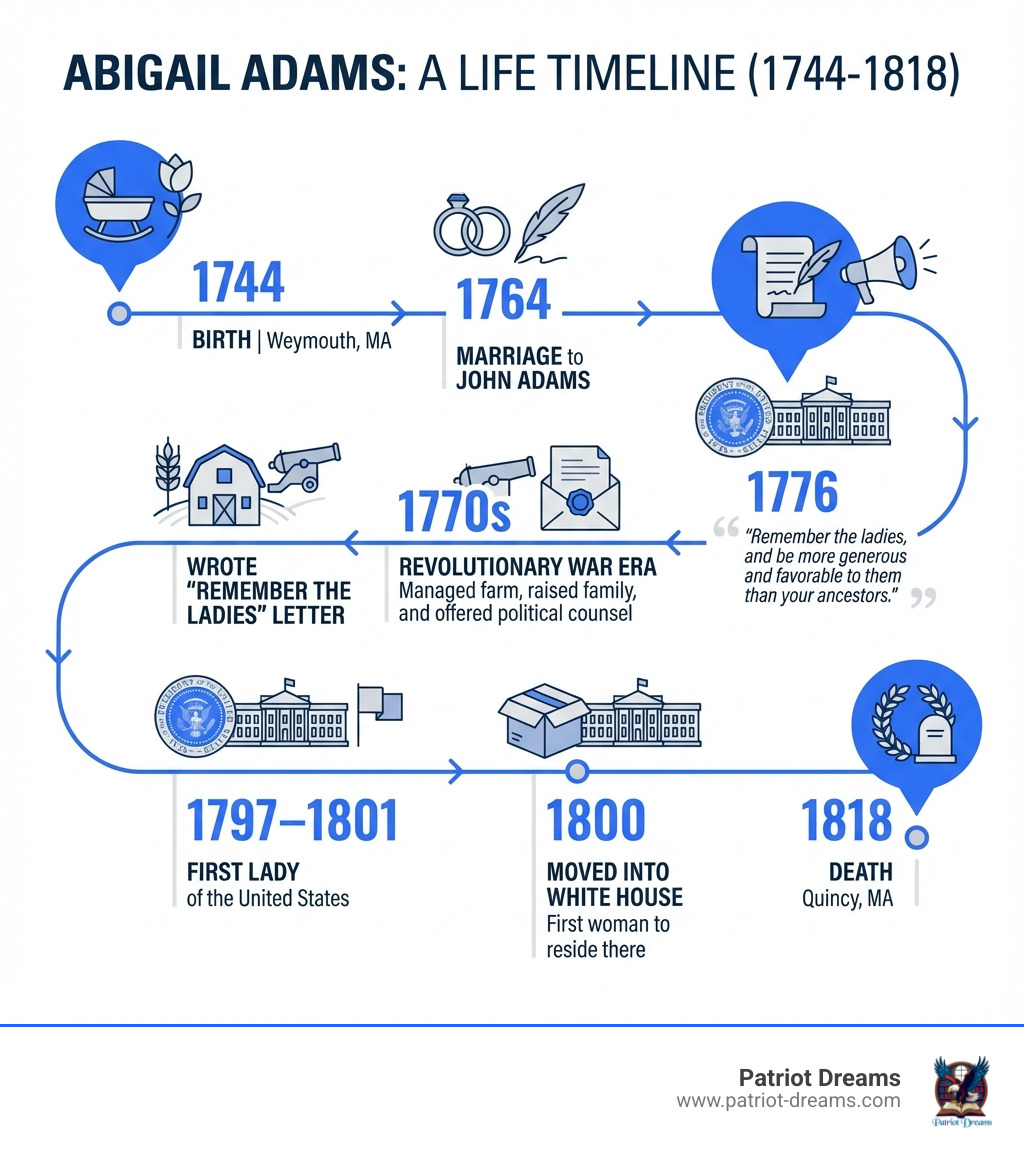

Quick Facts About Abigail Adams:

- Born: November 11, 1744, in Weymouth, Massachusetts

- Died: October 28, 1818, in Quincy, Massachusetts (age 73)

- Married to John Adams: 54 years (1764-1818)

- Children: Six (four survived to adulthood)

- Letters written to John: More than 1,100

- Role: First Lady from 1797-1801

- Famous for: Her "Remember the Ladies" letter advocating for women's rights

- Historic distinction: First woman to live in the White House

Abigail Adams lived during one of the most exciting and challenging times in American history. While her husband helped shape the new nation from Philadelphia and Europe, she managed their farm in Massachusetts, raised their children alone, and offered political wisdom that John valued above almost any other counsel.

Her letters paint a vivid picture of life during the American Revolution. She witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from a hilltop with her young son. She melted down the family's pewter dishes to make bullets for soldiers. And in her most famous letter, written in March 1776, she urged her husband and the Continental Congress to "remember the ladies" as they crafted laws for the new nation.

What makes Abigail's story so moving is not just her intelligence or her role in history. It's her warmth, her devotion to her family, and her unwavering belief that all people—including women and enslaved individuals—deserved education, dignity, and freedom. She was a woman ahead of her time, yet deeply rooted in the values of kindness, hard work, and service that built America.

Her life reminds us that greatness doesn't always wear a uniform or stand at a podium. Sometimes it writes letters by candlelight, tends to the sick, and quietly plants seeds of change that bloom for generations to come.

Key terms for Abigail Adams:

- Early American history

- Revolutionary War heroes

- Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence: How a Nation Found Its Voice

A Foundation of Strength: Early Life and Education

Abigail Adams began her journey in Weymouth, Massachusetts, on November 11, 1744. She was the second child born to Reverend William Smith, a Congregational minister, and Elizabeth Quincy Smith, who hailed from the prominent Quincy family. Growing up in a parsonage meant a life rich in intellectual and spiritual pursuits, even if it didn't include formal schooling.

In the 18th century, it was quite common for girls, especially in New England, to be educated at home rather than in formal schools, which were typically reserved for boys. Abigail, being frequently sick as a child, spent much of her early life at home. But this didn't deter her thirst for knowledge. Instead, she found her classroom within the extensive family library, a treasure trove of books that became her private university. She immersed herself in the works of literary giants like Shakespeare, John Milton, and Alexander Pope, cultivating a sharp mind and a love for language that would define her later years.

Her parents instilled in her a deep respect for God and a strong sense of community responsibility. She often accompanied her mother on visits to the sick and needy, learning compassion and the importance of helping others from a young age. These early experiences, combined with her self-education, shaped Abigail Adams into a woman of profound intellect, empathy, and resilience, qualities that would serve her, her family, and her burgeoning nation throughout her extraordinary life. She later reflected on her lack of formal schooling, understanding that it was a societal limitation placed upon women, but she never let it limit her intellectual growth.

A Partnership for a New Nation: Marriage and Family

In 1764, at the age of 19, Abigail Smith married John Adams, a young lawyer with a promising future. Their union marked the beginning of a remarkable 54-year marriage, a true intellectual partnership that would profoundly influence both their lives and the course of American history. John Adams quickly recognized Abigail's sharp intellect and relied heavily on her counsel, famously stating, "I never wanted your Advice and assistance more in my Life."

Their marriage was not just a personal bond; it was a foundational pillar for a new nation. While John dedicated himself to the cause of independence, often spending more than half their married life apart, Abigail managed their family farm in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts. She was responsible for the household, the children, and the complex financial affairs of the estate. This practical experience gave her a keen understanding of economics and property management, skills that were crucial for their family's prosperity and survival during turbulent times. She made shrewd investment decisions, ensuring their financial independence despite the limited property rights afforded to married women of that era.

Together, they had six children, four of whom, including their eldest son John Quincy Adams, reached adulthood. Their correspondence, a collection of over 1,100 letters, serves as a testament to their deep emotional connection and intellectual collaboration. These letters offer a rare glimpse into the personal sacrifices and political machinations of the Revolutionary era, filled with discussions ranging from philosophy and politics to the daily struggles of managing a household during wartime. It's a truly unique window into the hearts and minds of two of America's most influential founders. You can explore The Adams Family Correspondence to read some of these fascinating exchanges.

The Heart of the Revolution from Home

While John Adams was away at the Continental Congress, making history in Philadelphia, Abigail Adams was at home, living through history itself. She became an eyewitness to the American Revolution from a perspective few men experienced. From Penn's Hill, she and her young son, John Quincy, watched the smoke rise from the Battle of Bunker Hill, a stark and unforgettable reminder of the fight for freedom raging around them.

The war brought immense hardship and sacrifice. Abigail faced wartime shortages and crippling inflation, yet she managed the farm with remarkable efficiency, often with minimal help. In a poignant act of patriotism and practicality, she melted down the family's pewter dishes to be molded into bullets for the Continental Army, a vivid demonstration of her unwavering commitment to the cause.

Her contributions extended beyond managing the home front. The Massachusetts Colony General Court, recognizing her intelligence and sound judgment, even appointed her to question women suspected of loyalist sympathies. This was a quasi-official governmental role, showcasing the trust and respect she commanded in her community.

Through it all, she was raising her children alone, navigating the uncertainties and dangers of war with courage and grace. Her letters to John were not just personal updates; they were detailed reports on public sentiment, economic conditions, and the morale of the people. She offered astute political advice, serving as John's trusted confidante and an invaluable source of information from the heart of the colonies. Her steadfastness and dedication during these formative years were truly heroic, embodying the resilience of countless unsung Revolutionary War Heroes.

A Voice for the Future: Abigail Adams's Enduring Ideas

Abigail Adams was not merely a supportive wife; she was a profound thinker with enduring ideas that challenged the norms of her time. Her passionate advocacy for women, her clear opposition to slavery, and her unwavering belief in the power of education for all set her apart as a truly progressive voice in early America. She possessed a keen political mind, actively engaging with the great debates of the era and shaping discussions with her insightful perspectives, all of which contribute to our rich American Cultural History.

"Remember the Ladies": A Call for Representation

Perhaps no words of Abigail Adams resonate more powerfully today than those found in her letter of March 31, 1776, to her husband, John. As the Continental Congress deliberated the foundational laws of the new nation, Abigail penned a plea that would echo through centuries:

"I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the Ladies we are determined to foment a Rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice or Representation."

This wasn't just a request; it was a bold declaration of principles, urging the Founding Fathers to consider the rights of women in the nascent republic. Abigail believed deeply that women were entitled to the same rights as men—for education, property, and protection under the law. She strongly objected to the existing legal codes that prevented married women from owning property, highlighting the inherent injustice of such limitations. Her letter was a direct challenge to the patriarchal structures of the time, asserting that women should not be bound by laws in which they had no voice or representation. John Adams, in his response, playfully dismissed her call for an "extraordinary code of laws," yet the seriousness of her message was not lost, and her words became a timeless articulation of the struggle for gender equality. You can Read the original letter to feel the full impact of her powerful message.

A Stance on Liberty and Education for All

Abigail Adams extended her vision of liberty and equality beyond gender to include a principled stance against slavery. She viewed the institution of slavery as a fundamental threat to American democracy, questioning the very sincerity of those who championed freedom while denying it to others. Her anti-slavery beliefs were progressive for her era, even though her own family had been slaveholders. She demonstrated her convictions through action, notably in 1791 when she took a free Black youth into her Philadelphia home to teach him to read and write, despite objections from neighbors. This act underscored her belief that education and opportunity should be accessible to all, regardless of race.

Her advocacy for education was central to her philosophy. Abigail believed that educated women were essential for the strength of the nation. She saw mothers not just as caregivers, but as the primary shapers of future citizens, responsible for instilling virtue and knowledge in their children. This conviction drove her to ally with figures like Judith Sargent Murray, who also championed expanded educational opportunities for women. For Abigail, education was the key to intellectual independence and the ability to contribute meaningfully to society, echoing the very spirit of liberty that fueled the drafting of the Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence: How a Nation Found Its Voice.

A Life of Public Service: Diplomat's Wife and First Lady

Abigail Adams's life was one of constant public service, a journey that took her from the quiet farms of Massachusetts to the busy capitals of Europe and, finally, to the nascent seat of American power. Her diplomatic skills and social graces were first honed abroad as a diplomat's wife. From 1784 to 1788, she accompanied John to Europe, initially in Paris and then in London. While she found the initial demands of running a large household in Paris overwhelming, she soon accepted the vibrant cultural life, enjoying the theater and opera. However, she often expressed a dislike for London society, finding it less congenial than she had hoped. During this time, she even became a temporary guardian to Thomas Jefferson's daughter, Mary (Polly), forging a unique bond.

Upon their return to America, she continued her public role as the wife of the first Vice President, a position that, while not officially titled, effectively made her the first "Second Lady" of the United States. Her experience in European courts and society proved invaluable as she played a significant role in official entertaining, helping to establish the social protocols for the new federal government.

When John Adams became the second President of the United States in 1797, Abigail Adams stepped into the role of First Lady. She brought more intellect and ability to the position than almost any other woman in history. She was far from a ceremonial figure; her political acumen was widely recognized, earning her the nickname "Mrs. President" from her opponents. She actively hosted social events in Philadelphia, the temporary capital, to garner support for her husband's administration and vigorously defended his policies, including the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, through both private correspondence and public commentary. Her time as First Lady from 1797 to 1801 was marked by her insightful engagement with the political landscape and her unwavering dedication to her husband's career.

The First Inhabitants of the White House

One of the most iconic moments of Abigail Adams's tenure as First Lady was her move to the nation's new capital, Washington D.C., in November 1800. The experience was far from glamorous. The presidential mansion, now famously known as the White House, was still very much under construction, primitive and unfinished. Abigail famously described the conditions, lamenting the lack of firewood and the general state of disarray.

Despite the challenges, she approached her new home with her characteristic practicality and resilience. In one oft-recounted anecdote, with the East Room unfinished and lacking proper amenities, Abigail reportedly used it to hang her family's laundry. This small detail paints a vivid picture of the stark realities faced by the first occupants of what would become one of the world's most recognizable buildings.

Nevertheless, Abigail Adams quickly set about establishing the traditions and social customs of the presidential residence. She hosted the very first New Year's Day reception in the White House in 1801, beginning a tradition that continues to this day. Her presence marked a significant milestone: she was the first woman to live in the White House, literally setting the stage for future First Ladies. Her personal touch and determination helped transform a raw construction site into a functioning home and symbol of national leadership. To learn More about her time as First Lady, you can visit the White House Historical Association.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

After John Adams's loss in the 1800 election, Abigail Adams returned to their beloved Peacefield farm in Quincy, Massachusetts. While the political defeat was a source of bitterness for John, Abigail found a measure of contentment in retirement, as it meant an end to the painful separations that had defined so much of their married life. She continued to manage the household and maintain a robust correspondence, including a poignant reconciliation with Thomas Jefferson after years of political estrangement, a testament to her capacity for forgiveness and enduring friendship.

Even in retirement, Abigail remained a matriarch of a budding political dynasty. She closely followed the career of her son, John Quincy Adams, offering him guidance and encouragement, though she would not live to see him become the sixth President of the United States. Her life was filled with love, purpose, and an unyielding commitment to her family and country. She passed away on October 28, 1818, at the age of 74, after suffering from typhoid fever. Her last words to John were reportedly, "Do not grieve, my friend, my dearest friend. I am ready to go. And John, it will not be long." John, devastated by her loss, famously remarked, "I wish I could lay down beside her and die too."

A Quiet Return to Quincy and the Legacy of Abigail Adams

The period after John Adams's presidency allowed Abigail Adams to enjoy a quieter life back at Peacefield, their family home in Quincy. While the political landscape might have shifted, her influence and wisdom remained central to her family. This time, free from the public eye of the presidency, brought a different kind of fulfillment. It was a return to the roots she cherished, a chance to be fully present with her loved ones, and to continue her intellectual pursuits.

Her death in 1818 left a profound void, not just in her family but in the hearts of those who knew her. She was laid to rest at the United First Parish Church in Quincy, Massachusetts, alongside her beloved John, who would follow her in death eight years later. This church, a significant historical landmark, is a place where we can reflect on the lives of these two extraordinary figures. You can learn more about this historic site at the National Register of Historic Places Inventory – United First Parish Church.

The story of Abigail Adams is a powerful reminder that even in quieter moments, great legacies are forged. Her personal strength, intellectual curiosity, and unwavering spirit continued to inspire her family and community until her last days. She stands as a remarkable figure in Abigail Adams.

How We Remember Abigail Adams Today

Today, Abigail Adams is rightly celebrated as one of the most influential and remarkable women in American history. Her lasting legacy is multifaceted, deeply embedded in the fabric of our nation's story. In 1976, she was honored with induction into the National Women's Hall of Fame, a fitting tribute to her trailblazing spirit.

She is remembered as a voice for the voiceless, particularly for her early and eloquent advocacy for women's rights and education. Her "Remember the Ladies" letter remains a cornerstone document in the history of American feminism, continuously inspiring new generations to seek justice and equality.

Her extensive correspondence, more than 1,100 letters to her husband alone, is a national treasure. These letters offer an unparalleled eyewitness account of the birth of a nation, providing intimate details of the American Revolution, the challenges of forming a new government, and the daily lives of its founding families. Historians consistently rank her among the top three most highly regarded First Ladies, acknowledging her intellectual prowess, her political insights, and her profound impact on her husband's career and the early republic.

Abigail Adams stands as a model of partnership and resilience. Her life demonstrates how an individual, even without formal political office, can significantly shape history through intelligence, conviction, and tireless dedication. From her portrayal on a U.S. Mint First Spouse gold coin to her inclusion in significant art installations like Judy Chicago's "The Dinner Party," her image and words continue to resonate, reminding us of the enduring power of a thoughtful and courageous heart. For a deeper dive into her life and contributions, explore A biography from the National Women's History Museum.

Frequently Asked Questions about Abigail Adams

What is Abigail Adams most famous for?

Abigail Adams is most famous for her insightful and extensive correspondence, especially her letters to her husband, John Adams. Her March 1776 letter urging him to "Remember the Ladies" is a landmark document in the history of women's rights in America, demonstrating her early advocacy for greater legal protections and representation for women.

How did Abigail Adams influence her husband, John Adams?

She was his most trusted advisor and confidante. Through more than 1,100 letters, she offered counsel on politics, managed their family's finances and farm, and provided the emotional support that sustained him through the American Revolution and his presidency. John Adams frequently sought her opinions, valuing her judgment and insight immensely.

Was Abigail Adams the mother of a president?

Yes, she was the mother of John Quincy Adams, the sixth President of the United States. She is one of only two women in American history to be both the wife of a U.S. President and the mother of another, highlighting her family's remarkable contribution to American political leadership.

Conclusion: The Enduring Light of Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams's story is one of intelligence, resilience, and quiet strength. She was a partner in the founding of a nation, a loving mother, and a forward-thinking woman whose ideas on liberty and equality still resonate with us today. Her life reminds us that history is made not only on battlefields and in congress halls, but also in the thoughtful words and steadfast hearts of people like her. The stories of America's founding generation, full of personal courage and hope, are the very kinds of legacies we cherish and share at Patriot Dreams. Explore more stories from America's founding.

Join the Patriot Dreams Community

Download the app today and start your journey through American history and personal legacy.

Explore Our Latest Insights

Dive into stories that shape our American legacy.