The Declaration of Independence: What It Really Says and Why It Still Matters

Why the Declaration of Independence Remains America's Most Important Document

The Declaration of Independence: What It Really Says and Why It Still Matters is a question that goes to the heart of American identity. This founding document, adopted on July 4, 1776, serves as both America's birth certificate and a manifesto that changed the world forever.

What the Declaration Really Says:

- Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness are unalienable rights given by God

- All men are created equal – a radical idea in 1776

- Governments get their power from the people – not from kings or nobles

- 27 specific complaints against King George III proving tyranny

- The right to revolution when government fails the people

Why It Still Matters Today:

- Sets the moral standard for American democracy

- Inspired global freedom movements for over 200 years

- Provides the philosophical foundation for civil rights advances

- Remains a living document that challenges each generation

The Declaration wasn't just a breakup letter to Britain. Thomas Jefferson and the Continental Congress crafted a document with three audiences in mind: King George III, the American colonists, and the entire world. They needed to justify rebellion, rally troops, and win foreign allies—all in one powerful statement.

What makes this document extraordinary isn't just what it said, but how its meaning has evolved over time. The phrase "all men are created equal" has been reinterpreted by abolitionists, suffragettes, and civil rights leaders to expand freedom for all Americans.

The Road to Independence: "An Expression of the American Mind"

To understand the Declaration, we must look at the historical events that led to its creation. Discontent in the American colonies simmered for years, boiling over with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. Initially, colonists sought rights within the British Empire, not separation. But as conflict grew and King George III declared the colonies in rebellion, the call for independence strengthened.

The Second Continental Congress, convening in May 1775, became the center of colonial resistance. The push for a central government and the ongoing military conflict moved the colonies toward independence. Rhode Island was the first to renounce allegiance to the King, and by May 1776, North Carolina and Virginia had authorized their delegates to vote for it. This growing support showed a shift in the "American mind," a phrase Thomas Jefferson later used to describe the Declaration's origins.

The Committee of Five: The Minds Behind the Masterpiece

As independence calls grew, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution on June 7, 1776, stating the colonies "ought to be, free and independent States." The vote was postponed, but Congress appointed a "Committee of Five" to draft a formal declaration: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, and Thomas Jefferson.

Though a team effort, Jefferson wrote the first draft between June 11 and June 28, 1776, in a rented Philadelphia room. His "original Rough draught" was heavily revised. Adams and Franklin made suggestions, and the Continental Congress made 86 changes, shortening it by over a fourth. Notably, a passage condemning the slave trade was removed to secure unanimous support from Southern colonies. This collaborative process reveals the high political and philosophical stakes involved.

From Resolution to Reality: The Vote for Freedom

On July 2, 1776, Congress approved Lee's resolution for independence. John Adams believed this would be America's most memorable day. Two days later, on July 4, 1776, Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence, the document explaining why they were taking this step.

Contrary to popular belief, no one signed the Declaration on July 4. The official handwritten or "engrossed" copy wasn't ready until August. Most of the 56 delegates signed it on August 2, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall). John Hancock, President of the Congress, signed with a large flourish, making his name a synonym for a signature. Two delegates, John Dickinson and Robert R. Livingston, never signed.

Upon adoption, John Dunlap printed about 200 broadside copies for distribution. Public readings across the colonies were met with fanfare. After a reading in New York on July 9, 1776, colonists pulled down a statue of King George III, melting parts of it into bullets—turning a symbol of oppression into instruments of liberation.

Deconstructing the Declaration: What It Really Says

When we look at The Declaration of Independence: What It Really Says and Why It Still Matters, we find it's more than a breakup letter to Britain; it's a sophisticated political document crafted for multiple purposes.

Think of the Declaration as three documents in one: a legal indictment of the King, a philosophical statement on human rights, and a declaration of war. Jefferson and the Continental Congress wrote it for three distinct audiences: King George III, the American colonists, and the world, especially potential allies like France.

The document has three main parts: the Preamble, a list of 27 grievances, and the final resolution of independence. Each section builds the case that revolution was not just justified, but necessary.

The Preamble: A Timeless Statement of Human Rights

The opening lines are among the most powerful ever written: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

The term "self-evident" means the truths carry their own evidence; the truth is inherent in the claim. The idea that "all men are created equal" was radical in 1776. In a world of kings and nobles, the Founders asserted that all humans share a common nature, giving them the same basic rights regardless of birth.

These "unalienable Rights" (which can't be taken away) were inspired by thinkers like John Locke. Jefferson's addition of the pursuit of Happiness was uniquely American, meaning the right to live a flourishing, meaningful life, not just personal pleasure.

The Preamble also claims government power comes "from the consent of the governed," replacing the divine right of kings. If a government fails, the people have "the right to revolution." This philosophy justified the colonists' actions.

The Indictment: 27 Grievances Against the King

After the Preamble, the Declaration lists 27 specific complaints against King George III, making the case that he was a tyrant. These complaints demonstrated a "long Train of Abuses"—a deliberate pattern of oppression designed to destroy colonial freedom.

The grievances included legislative violations like refusing to approve necessary laws, judicial obstruction by making judges dependent on the King, and military oppression like keeping standing armies in peacetime.

Economic exploitation included "taxation without representation" and cutting off trade. Most seriously, the King committed acts of war against his subjects: burning towns, hiring foreign mercenaries, and encouraging attacks on the frontier.

This long list of complaints served as "a case for the world," proving the rebellion was a justified last resort under international law and natural rights.

The Resolution of Independence: "These United Colonies are... Free and Independent States"

The Declaration concludes with its powerful resolution: "That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States." This severed all political ties with Britain, and the colonies claimed their place as a sovereign nation.

The most powerful part is the final pledge. The 56 signers knew they were committing treason, a crime punishable by death. They concluded with the solemn vow: "We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor."

This was no empty rhetoric. The signers bet everything on freedom. With those words, the United States of America was born as a nation whose founders were willing to die for it.

The Declaration of Independence: What It Really Says and Why It Still Matters Today

The Declaration of Independence: What It Really Says and Why It Still Matters extends far beyond its 18th-century origins. This document has grown from a colonial breakup letter into a living blueprint for human freedom that continues to shape our world.

What makes the Declaration so enduring is that it established timeless principles and set a moral standard that America still strives to meet. Though not law itself, its principles of consent of the governed and natural rights provided the foundation for the Constitution, which became the "how" to the Declaration's "why."

Its impact also reaches far beyond American shores, inspiring countless nations. Leaders from Haiti to Vietnam have borrowed its language to justify their own fights for self-determination. What began as a statement on colonial rights has become an expanding promise, challenging each generation to live up to its ideals.

The Evolving Meaning of "All Men Are Created Equal"

The phrase "all men are created equal" has sparked endless debate and hope. In 1776, it was a radical idea that challenged a world built on rigid class systems. Yet, the Declaration carried a contradiction: Thomas Jefferson, its author, owned hundreds of enslaved people. He tried to include an anti-slavery passage in his draft, but Congress removed it to appease Southern colonies. This paradox of slavery would haunt America for generations.

Remarkably, the Declaration's words proved more powerful than its authors' limitations. People like Lemuel Haynes, a Black Revolutionary War veteran, used its language to argue against slavery. The abolitionist movement seized on this contradiction. In his 1852 speech, "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?", Frederick Douglass called the Declaration a "promissory note" that the nation had failed to honor.

The fight for equality expanded. At the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott issued their "Declaration of Sentiments," adapting the founders' words to declare "all men and women are created equal" and demand women's rights.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address reframed the conflict as a test of whether a nation "dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal" could survive. For Lincoln, the Declaration was an unfinished promise.

The Civil Rights Movement gave the words new power. In his 1963 "I Have a Dream" speech, Martin Luther King Jr. called the Declaration a "promissory note" and demanded America finally make good on its promise for all citizens. Today, the expansion continues as various rights movements push the boundaries of equality, a process that is profoundly American.

A Global Guide: The Declaration's International Impact

The Declaration of Independence didn't just create America—it changed the world, becoming a template for national independence. The founders wrote it for a global audience, using universal principles to win international support, especially from France. The strategy worked. The Franco-American Treaty of 1778 recognized the U.S. and turned the rebellion into a global conflict, with French support proving crucial for victory.

The global impact was just beginning. Haiti's 1804 declaration of independence, which also overthrew slavery, echoed the American document. Latin American independence movements in the early 1800s also drew on the American example, turning the Declaration into a blueprint. Even in the modern era, Ho Chi Minh opened Vietnam's 1945 Declaration of Independence with "All men are created equal."

Today, over half the world's nations have founding documents echoing the Declaration. It proved that self-determination is a universal human aspiration. The Declaration's global legacy shows that people everywhere are inspired by its message: that citizens have the right to self-governance and the pursuit of happiness.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Declaration of Independence

Many people have questions about this foundational document. Here are answers to some of the most common ones.

Who actually signed the Declaration on July 4, 1776?

It's a common myth that the Declaration was signed on July 4th. In reality, no one signed it on that date. On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration, approving its final text. The signing came later.

The formal engrossed copy (the handwritten version) wasn't ready until early August. Most of the 56 delegates gathered on August 2, 1776, to sign the parchment in Philadelphia, with a few signing even later. So, July 4th marks the Declaration's adoption, but the iconic signatures were added weeks afterward.

Is the Declaration of Independence a legally binding document?

The Declaration isn't a legally binding document like the Constitution. It cannot be used to win a court case, as judges do not cite it as binding law.

Instead, it is America's philosophical foundation—a statement of principles explaining the break from Britain and the new nation's ideals. However, the Declaration's influence on American law is profound. It laid the groundwork for the Constitution, which built a government based on its ideas of popular sovereignty, natural rights, and limited government.

It serves as our moral and philosophical standard—the "expression of the American mind," as Jefferson called it. While not enforceable in court, it guides our understanding of democracy and rights. It's the spirit behind our laws.

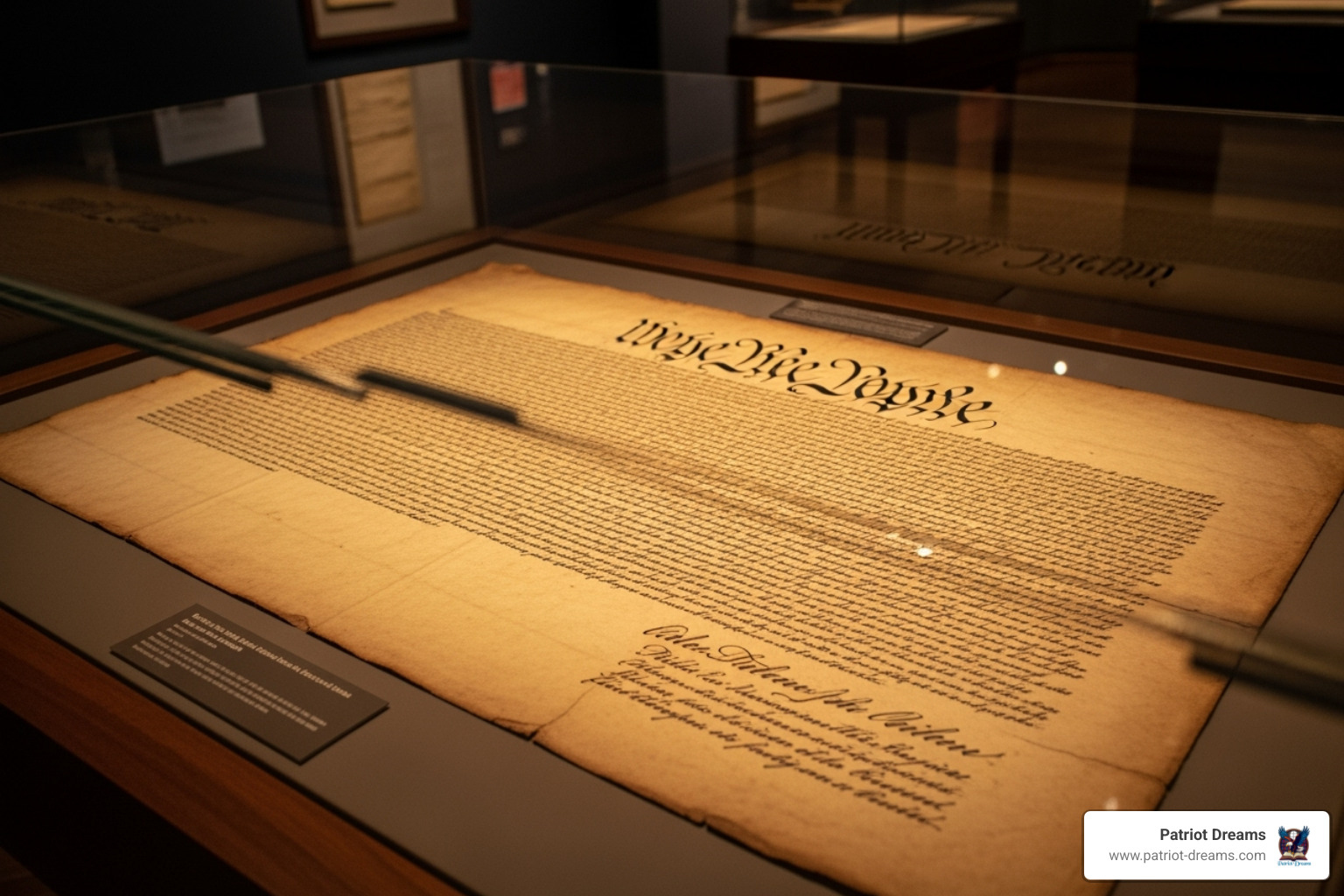

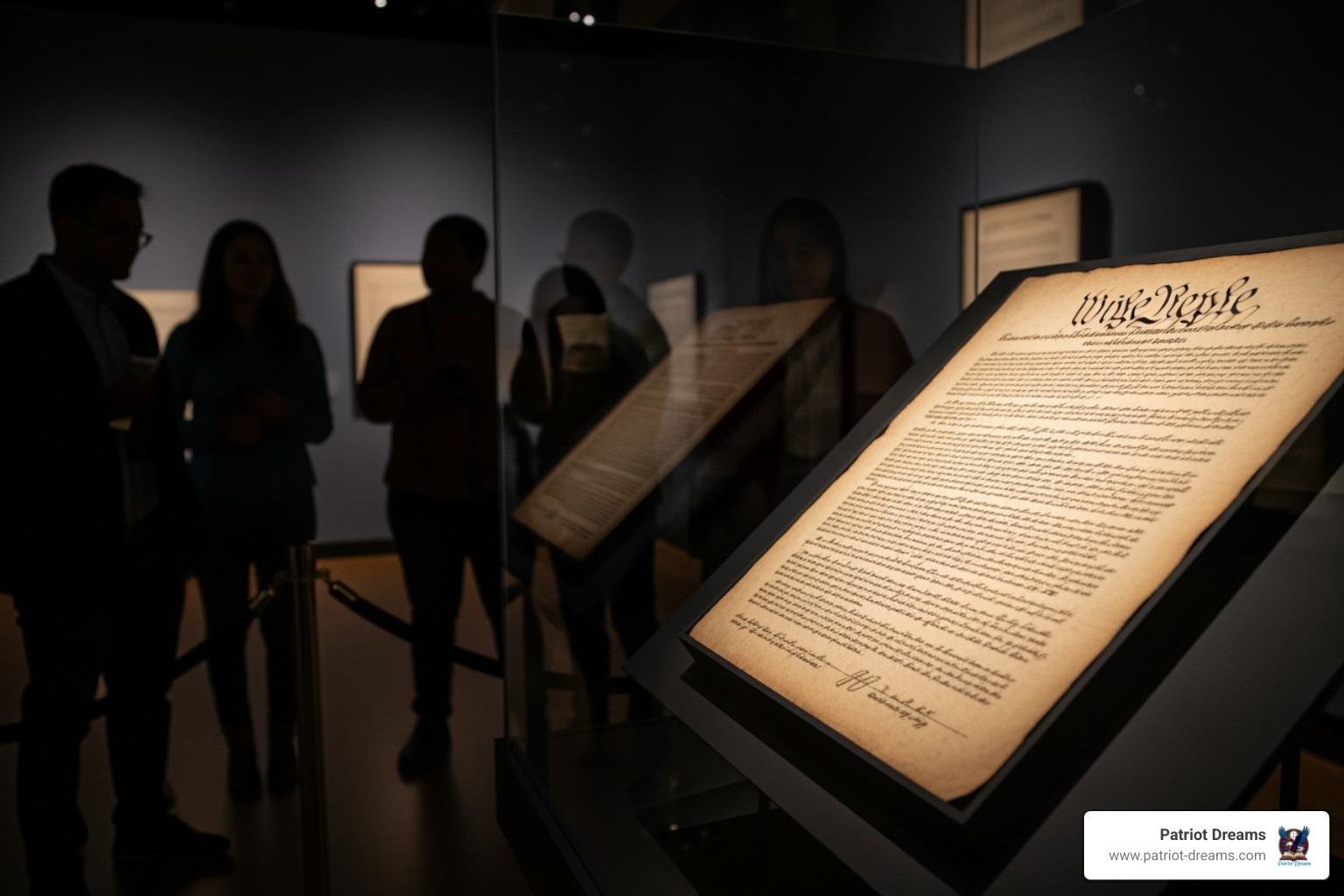

How has the Declaration of Independence been preserved?

The original parchment document has had a fascinating preservation history. After the signing, it traveled with the Continental Congress, and the constant movement and rolling contributed to early damage, including the fading ink. In the 19th century, efforts to create copies caused more damage by lifting ink off the original.

During World War II, it was secretly moved to the Bullion Depository at Fort Knox, Kentucky, for protection alongside the nation's gold reserves. Since 1952, it has resided at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., housed in a state-of-the-art preservation system.

The document is in a case of ballistically tested glass and plastic laminate, filled with protective argon gas. A sophisticated camera and computerized monitoring system watches over it 24/7, checking its condition to ensure its preservation for future generations. You can learn more and read the full text at the National Archives - Declaration of Independence: A Transcription.

Conclusion: The Enduring Promise of the Declaration

The Declaration of Independence: What It Really Says and Why It Still Matters takes us to the heart of what it means to be American. This remarkable document didn't just announce the birth of a new nation—it dared to imagine a world where ordinary people could govern themselves and claim rights that no king or government could take away.

From Thomas Jefferson's candlelit room in Philadelphia to the marble halls of the National Archives, the Declaration has traveled an incredible journey. What started as 27 specific complaints against King George III became something much larger—a blueprint for human freedom that has inspired liberation movements on every continent.

The three simple truths at its core remain as powerful today as they were in 1776: that we're all created equal, that we have God-given rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and that governments only have power when people give it to them. These weren't just nice-sounding words—they were ideas that turned the world upside down.

But perhaps what's most remarkable about the Declaration is how it's grown with us. The promise of equality that started with colonial grievances expanded to include enslaved Americans fighting for freedom, women demanding the vote, and countless others who saw their own struggles reflected in Jefferson's words. Each generation has had to wrestle with what "all men are created equal" really means—and that ongoing conversation is part of what keeps America vibrant.

The Declaration reminds us that freedom isn't a destination—it's a continuous journey. It's the foundation that everything else was built on, from the Constitution to the Civil Rights Movement. It's why people around the world still look to America as a guide of hope, even when we fall short of our own ideals.

At Patriot Dreams, we know these stories matter because they're your stories, too. The courage of those 56 signers who pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor echoes in every American who stands up for what's right. The Declaration isn't just history—it's a living promise that each of us inherits and helps fulfill.

Ready to find more stories that shaped our nation? Explore more pivotal moments in American history and see how the threads of courage, conviction, and hope weave through every chapter of the American story. Because understanding where we came from helps us figure out where we're going next.

Join the Patriot Dreams Community

Download the app today and start your journey through American history and personal legacy.

Explore Our Latest Insights

Dive into stories that shape our American legacy.